The hum of public health alerts has become an unwelcome soundtrack in Ontario, as a once-quelled adversary, measles, stages a disquieting comeback. With infection numbers climbing past 1,400 since October, the province finds itself grappling with a significant health challenge. This analysis delves into the anatomy of Ontario’s escalating measles situation, examining the critical role of vaccine hesitancy, the particular vulnerability of rural communities, and the determined, if strained, public health response.

Measles, a virus known for its aggressive transmissibility, was largely considered a relic of a bygone era in regions with robust vaccination programs. The current Canadian outbreak, with roots traced to a gathering in New Brunswick last fall, has found particularly fertile ground in Ontario. While some provinces, like Quebec, have managed to declare their outbreaks concluded, Ontario’s figures, updated as of May 10, 2025, paint a starkly different picture of an ongoing struggle. The province’s chief medical health officer, Dr. Kieran Moore, has pointed to a difficult truth: many affected communities have historically low rates of vaccination for themselves and their children.

The data speaks with a chilling clarity. Nearly 200 new cases were recorded in Ontario this past week alone, pushing the total to 1,440. This surge is not indiscriminate; it disproportionately affects unvaccinated infants, children, and teenagers, particularly within rural communities in southwestern Ontario. This pattern underscores a concerning trend where pockets of vaccine hesitancy can rapidly ignite wider transmission. The consequences extend beyond immediate illness, as evidenced by the suspension of 920 secondary school students in the Waterloo region due to outdated vaccination records—a measure reflecting the seriousness with which authorities view containment.

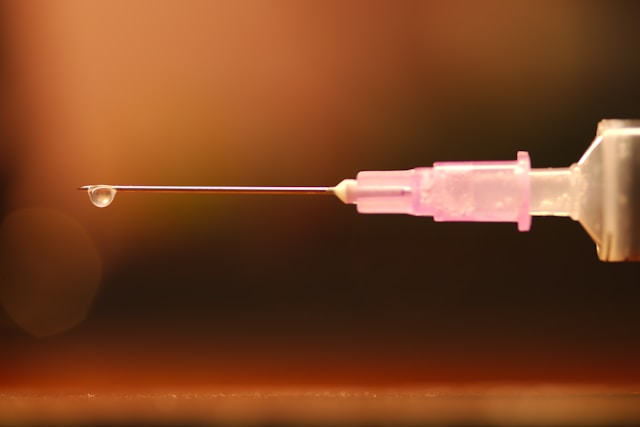

At the heart of this unfolding drama is the issue of vaccine hesitancy. Dr. Moore’s observation that “in the particular communities affected, they have historically not vaccinated themselves or their children,” highlights a deep-seated challenge that transcends simple information campaigns. This reluctance creates vulnerable populations, especially infants too young for the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, rubella, and, according to health officials, chicken pox. Edmonton pediatrician Dr. Tehseen Ladha offers a sobering reminder of the stakes, explaining that measles can lead to severe complications like encephalitis, or brain inflammation, potentially causing “long term disability in those children… blindness, seizures, brain damage.” The public health response, therefore, is multi-pronged, involving increased efforts to promote vaccine uptake and enforce existing immunization requirements for school attendance.

The implications of this sustained outbreak are considerable. Beyond the immediate health risks and the tragic potential for severe complications in children, the situation strains public health resources and fosters a climate of anxiety. The spread, particularly in rural communities, demonstrates how localized pockets of low immunization can undermine broader community protection. Dr. Moore’s simple yet profound statement, “Prevention is the best medicine, and we have very effective and safe vaccine against measles,” serves as a constant refrain from health authorities facing a tide of preventable illness. The efficacy of the two-dose MMR vaccine, typically administered at 12 and 18 months, is well-established, yet its uptake remains a critical hurdle.

Ontario’s current battle with measles is a stark illustration of how individual choices regarding vaccination can precipitate widespread public health consequences. The climbing case numbers serve as a grim tally of a challenge rooted in apprehension and misinformation. Addressing this crisis effectively requires not only robust medical intervention but also a concerted effort to rebuild trust in proven preventative measures, ensuring that the echoes of a preventable disease finally fade into silence. It’s a difficult conversation, but one Ontario must have to protect its most vulnerable and uphold the integrity of its public health shield.

References:

Here’s how measles cases are spreading across Canada